Byrdhouse Farm Bakery

Behind the spread of pies and breads at the Byrdhouse Farm booth, the friendly but shy baker Lucy Byrd is fairly reserved—until you start asking her about pie. It’s just the trigger she needs to jump start a discussion. Everywhere on social media, it seems, pies are trending, and she’s definitely got an opinion about that.

“I see people going for the showy, glitzy look instead of the real flavors and it just disappoints me. Pie is part of who we are. There’s a tradition here of flavor and richness. You need to go back to that. Eat real food.”

Lucy loves the farmers' market because it brings people together in search of a common goal: access to fresh, local food. “As a small farmer myself, I believe we need to be supporting each other, and I think that we need to be eating locally.”

For her baked goods, Lucy uses as many local ingredients as possible, striving for quality and authenticity. The woman even grinds her own whole wheat. It’s an old-fashioned principle that harkens back to a simpler time.

Devotees of old-fashioned pies are sure to delight in Lucy’s baked goods. Pie is so central to her life that she skipped the whole wedding cake business and instead opted for 20 fruit pies and homemade ice cream. It might sound unusual, but it’s really. She comes from pie people.

When she was six years old, she stumbled into her grandmother’s kitchen on Thanksgiving Day and found all the women of her family—mother and aunts and sisters and cousins—gathered around a table, laughing and carrying on intimately over plates of pie. Lucy, who was a picky eater and didn't like pie at the time, asked what the fuss was all about.

They turned to look at her and said, “Sweetie. This is pie.”

To prove their point, they invited her to sit and someone placed a small plate of blueberry pie before her. “It was so good that it made the back of my tongue ache,” Lucy recalls. “The flavors… it changed my world.”

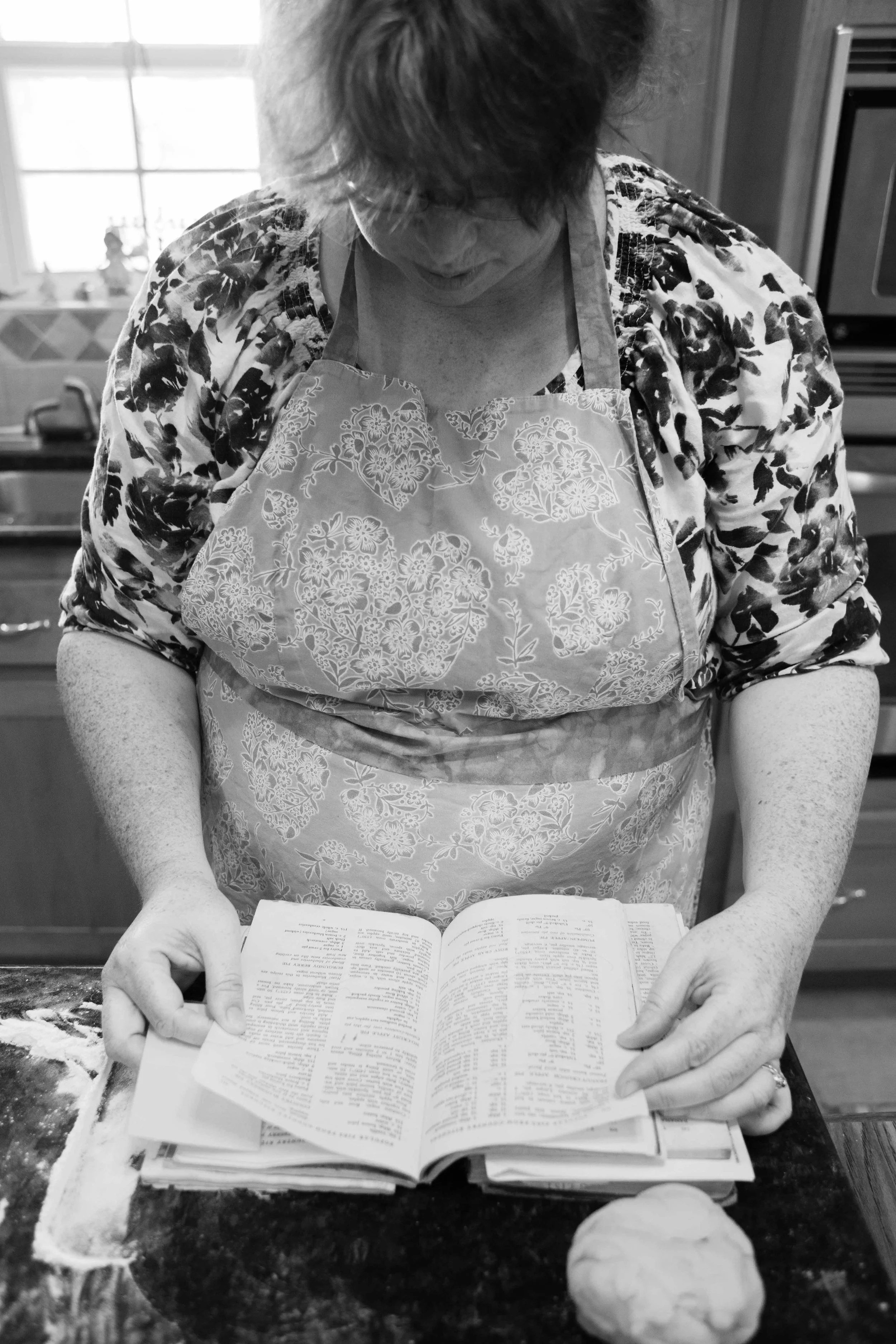

From then on, she was hooked. Today, she uses that very same blueberry pie recipe for market. And her other pies—razzleberry, cherry, blackberry, peach, even sweet potato—all come handed-down from the women of her earlier generations. She has her mother’s cookbooks, time-honored and dog-eared, worn at the seams, marked, stained, smeared with use. She consults the recipes of her grandmother, born in 1895, which are often little more than a list of ingredients.

Heritage matters, but quality matters, too, and that’s what Lucy finds in these antique instructions.

Old recipes ask for more natural ingredients—honey as opposed to corn syrup in pecan pie, for example. “Old pies are less sweet and [have] more flavor. They always taste better. You can taste better. I have people that come back to the booth all the time and say, ‘That pie tasted like the pie my great-grandmother used to make.’ And I say, ‘That’s because it comes from the recipes that your great-grandmother used to use.’ That is the best compliment. It makes my day.”